When we think of PEDs origins in baseball, we often think of José Canseco. However, what Canseco did in the 1980s technically wasn’t forbidden in baseball, officially. It was then-Commissioner Fay Vincent who specifically outlawed the use of performance-enhancing drugs in a 1991 memo to all MLB entities. However, Vincent was forced from office by an owners’ coup, led by Bud Selig. We’re not defending Canseco—ever.

It’s ironic and telling that Selig’s run as commissioner saw the use of PEDs in the sport explode, as too many fans sadly didn’t seem to care if their heroes and teams were cheating. This has continued through the era of Rob Manfred as MLB commissioner, sadly, with other cheating scandals joining in the fray as teams chased profits and successes without ethics, integrity, or morality in mind. And the money? Keeps coming.

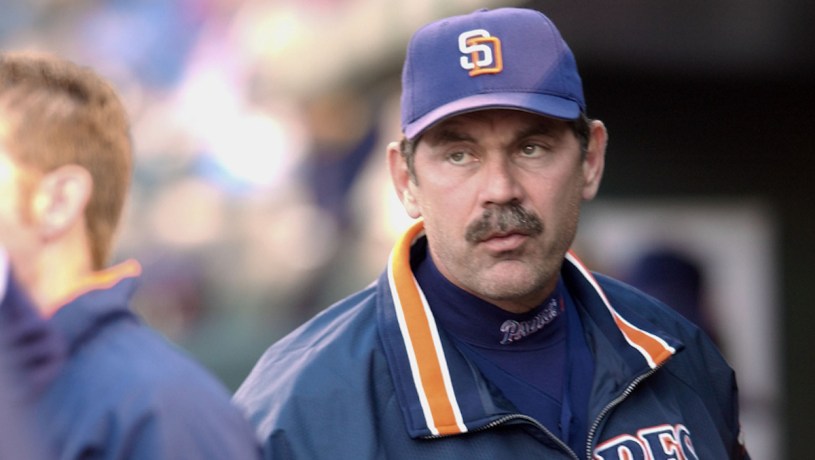

Back in the mid-1990s, Manager Bruce Bochy was running the San Diego Padres, a franchise that had hit rock bottom since making the World Series in 1984 with a mediocre backup catcher named … Bruce Bochy. After that surprise run to the Fall Classic, the organization fell on hard times over the subsequent 10 seasons, finishing an average of 17 games out of first place through 1994’s strike-shortened season.

Enter Bochy the manager in 1995, and suddenly, the Padres won the NL West for the first time since 1984 in just Bochy’s second season as manager in 1996—thanks to the voted-MVP season of third baseman Ken Caminiti. Well, we know how this turned out: Caminiti later admitted to taking steroids, and he died a young death as a result of a lot of complications stemming from his actions with PEDs and the Padres.

Somehow, Bochy has escaped all culpability in this matter; how, we cannot understand. According to many reports, Caminiti loved Bochy—for reasons we can only guess, although perhaps the primary one is that Bochy enabled his PED use and saved his career while making him a millionaire. Prior to joining the San Diego organization in 1995, Caminiti was a mediocre player over 8 seasons with the Houston Astros.

Through age 31 in 1994, the best season Caminiti had ever produced was a surprising All-Star season his final year in Houston (.847 OPS). Before that, he’d never cracked the .800 OPS barrier. And then in San Diego, on PEDs under the tutelage of Bochy, Caminiti suddenly put together four seasons from ages 32-35 with a combined .924 OPS. We know he was on drugs; we know he was past his prime; we see the effect here.

It’s probable that at age 31 with a mediocre career, Caminiti took PEDs his last year with the Astros in order to score a good free-agent deal to finish his career. He signed with the Padres for almost a 50-percent raise immediately—and a four-year, $14.5M deal overall—for an age-32 player with one All-Star season under his belt. If Bochy had his star player’s back, he knew he was cheating. This could not have escaped a manager.

And it worked: Bochy got the team to the playoffs in 1996 and the World Series again in 1998, although the Padres didn’t win. At age 36 now, Caminiti left the Padres after that season, and his career petered out with the Astros, the Texas Rangers, and the Atlanta Braves. He was out of baseball by 2001, and San Diego went on to have five straight losing seasons with Bochy at the helm from 1999-2003 (average 25.7 games behind).

Bochy then had a front-row seat to watch the criminality in San Francisco with Giants PED user Barry Bonds. What was going through Bochy’s mind then? We can only guess, but it was probably something like this: “I had my best years with a known PED user as my star, and the Giants are now having their best years with a known PED user as their star. How do I get back to having a PED user as my team’s star?” Ahem.

In his last three years with San Diego (2004-2006), Bochy’s teams managed an aggregate 257-229 record and won two NL West Division titles in 2005 and 2006. How did he do it? Should we look at those rosters for suspect performances from fading, washed-up players who suddenly got better under Bochy’s managerial “touch”? Of course, we should (and we’re wondering why we’ve never done this before):

- 2004: A duo of 30-something hitters pulled off impressive seasons. First baseman Phil Nevin posted his best numbers (.859 OPS) in three years at age 33, and second baseman Mark Loretta posted his career-best numbers (.886 OPS) at age 32. The presence of former Bonds teammate Rich Aurilia on the roster certainly must have helped. Not surprisingly, Aurilia went back to S.F. after Bochy did. On the pitching side, age-41 starter David Wells posted his best ERA (3.73) since 1998. We know wells played with Roger Clemens in New York before this, so … yeah. Suspicions abound.

- 2005: Nevin and Loretta dropped off considerably this year, but never fear, other vets took their place with strange seasons at advanced ages. 1B Mark Sweeney saw his batting average rise 28 points from his previous season in Colorado—at age 35. This is almost identical to the Marco Scutaro Experiment in 2012, actually. At age 36, reliever Rudy Seanez pitched a career high in innings while also posting a career-low in ERA. No one pulls off a double double like that, naturally, that late in a career. These are just two of the prominent contributors to this playoff-qualifying squad that won just 82 games.

- 2006: There are some amusing connections on this roster, starting with catcher Mike Piazza, who we have never suspected of PED use before now. However, at age 37, Piazza put up his best OPS mark in a full season since 2002. Centerfielder Mike Cameron posted the best OPS of his career at age 33; SP Woody Willams had his best season since 2002, as well, in terms of ERA—at age 39. And RP Alan Embree, a veteran of the 2004 Boston Red Sox who we have identified already, posted his lowest ERA since 2002 at age 36. He may have actually picked up his MO in his first stint with Bochy in San Diego (2002). Or maybe it was Embree’s time with Bonds in San Francisco (1999-2001). Who knows? Dirty.

Plenty of examples to show Bochy’s success in San Diego, beyond Caminiti’s PED years, may have been driven by his PED enablement that continued after Caminiti left town before the 1999 season. The patterns above are the exact same as we have seen in close examination of the Red Sox and the Giants. The statistical anomalies do not lie: when players have sudden rebounds at old ages, it’s not natural at all. Never has been.

So, Bochy then left the Padres to take over a Giants team that had not posted a winning season since 2004 despite the presence of Bonds and other probable PED users on its rosters. We don’t need to recount Bochy’s tenure with the Giants, for we’ve done it before. The archives are there for anyone to peruse; we can now move on to this year’s Texas Rangers, as we took a cursory glance at this earlier this season already.

What are we to think now that the Rangers are in the World Series, despite all mathematical odds against it happening? The Rangers went 40-41 on the road this year, but then Texas won its first six road playoff games against Tampa Bay, Baltimore, and Houston—all teams that finished above them in the standings and were mathematically favored to win those games at home. That probability was less than 1 percent.

Beating the sign-stealing Astros four times on the road also defies all logic and mathematical probability. So, who on this Texas roster fits the above patterns, which are well established now throughout Bochy’s success in San Diego and San Francisco? We will let you guess: Bochy is a sub-.500 manager in his regular-season career (2093 wins, 2101 losses). Yet everyone thinks he’s a genius because of these quirky results.

A handful of “lucky” games in October, and people ignore the other 4,200 regular season games where’s he been mediocre. Talk about logical fallacies—it’s like no one here took Logic 101 in college. The above data analysis is really the only thing that makes sense. Texas went 18-24 down the stretch and almost missed the playoffs this year. They were 14-22 in one-run games, 2-8 in extra innings, and 40-41 on the road.

These are all signs of a poorly managed team, despite its $251M payroll. Bochy doesn’t have a magic switch he suddenly flips in October; it doesn’t work that way. He almost cost a high-payroll team its playoff spot, and now he’s going to take the credit for them getting to the Series? That makes no sense whatsoever except to people who have no critical-thinking skills at all. Remember, even Joe Torre was a bad manager (.471) …

Until he got handed the reins of the high-spending Yankees. Then suddenly he was a genius. Same issue here; facts are facts, and Bochy is not a genius, or else he’d be over .500 in the 4,200 regular-season games he’s managed through this season. He’s not: he’s a sub-.500 manager. It’s mathematics: a few small samples in October do not change the fact he’s a losing manager (2093 wins, 2101 losses).

Plus, in the end, there’s always this fact from basic psychology: if an individual or an organization is not punished for illegal, immoral, or unethical behavior without suffering severe consequences, that entity will not change its behavioral decisions and patterns. Colloquially, tigers cannot change their stripes. Bochy always has been a PED enabler, and he’s never been called out for it … until now. We know what he really is.

To repeat what a childhood friend of ours recently stated, “I could talk baseball all day, anytime. I just can’t watch the current state of pro ball.” Us, neither. We’re done.

While you were writing this, Bochy just added his fourth World Series ring. Do you really think they won because he enabled his Rangers to use PED’s? I think you’re drawing too many conclusions because of the broad history of baseball, rather than him personally. He’s a great manager who inspires confidence. He knows how to win. Is luck a part of it? For sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person